Despite decades of effort, scientists do not know what “number”—in terms of temperature or concentrations of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere—constitutes a danger. When it comes to defining the climate’s sensitivity to forcings such as rising atmospheric carbon dioxide levels, “we don’t know much more than we did in 1975,” says climatologist Stephen Schneider of Stanford University, who first defined the term “climate sensitivity” in the 1970s.

“What we know is if you add watts per square meter to the system, it’s going to warm up.” Greenhouse gases add those watts by acting as a blanket, trapping the sun’s heat. They have warmed the earth by roughly 0.75 degree Celsius over the past century. Scientists can measure how much energy greenhouse gases now add (roughly three watts per square meter), but what eludes precise definition is how much other factors play a role—the response of clouds to warming, the cooling role of aerosols, the heat and gas absorbed by oceans, human transformation of the landscape, even the natural variability of solar strength.

“We may have to wait 20 or 30 years before the data set in the 21st century is good enough to pin down sensitivity,” says climate modeler Gavin Schmidt of the NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies. Despite all these variables, scientists have noted for more than a century that doubling preindustrial concentrations of CO2 in the atmosphere from 280 parts per million (ppm) would likely result in global average temperatures roughly three degrees C warmer. But how much heating and added CO2 are safe for human civilization remains a judgment call.

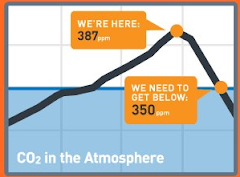

European politicians have agreed that global average temperatures should not rise more than two degrees C above preindustrial levels by 2100, which equals a greenhouse gas concentration of roughly 450 ppm. “We’re at 387 now, and we’re going up at 2 ppm per year,” says geochemist Wallace Broecker of Columbia University. “That means 450 is only 30 years away. We’d be lucky if we could stop at 550.”

Goddard’s James Hansen argues that atmospheric concentrations must be brought back to 350 ppm or lower—quickly. “Two degrees Celsius [of warming] is a guaranteed disaster,” he says, noting the accelerating impacts that have manifested in recent years. “If you want some of these things to stop changing—for example, the melting of Arctic sea ice—what you would need to do is restore the planet’s energy balance.”

Other scientists, such as physicist Myles Allen of the University of Oxford, examine the problem from the opposite side: How much more CO2 can the atmosphere safely hold? To keep warming below two degrees C, humanity can afford to put one trillion metric tons of CO2 in the atmosphere by 2050, according to Allen and his team—and humans have already emitted half that.

Put another way, only one quarter of remaining known coal, oil and natural gas deposits can be burned. “To solve the problem, we need to eliminate net emissions of CO2 entirely,” Allen says. “Emissions need to fall by 2 to 2.5 percent per year from now on.”

Climate scientist Jon Foley of the University of Minnesota, who is part of a team that defined safe limits for 10 planetary systems, including climate, argues for erring on the side of caution. He observes that “conservation of mass tells us if we only want the bathtub so high either we turn down the faucet a lot or make sure the drain is bigger.

An 80 percent reduction [in CO2 by 2050] is about the only path we go down to achieve that kind of stabilization.” The National Academy of Sciences, for its part, has convened an expert panel to deliver a verdict on the appropriate “stabilization targets” for the nation, a report expected to be delivered later this year. Of course, perspectives on what constitutes a danger may vary depending on whether one resides in Florida or Minnesota, let alone the U.S. or the Maldives.

Keeping atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gases below 550 ppm, let alone going back to 350 ppm or less, will require not only a massive shift in society—from industry to diet— but, most likely, new technologies, such as capturing CO2 directly from the air. “Air capture can close the gap,” argues physicist Klaus Lackner, also at Columbia, who is looking for funds to build such a device.

Closing that gap is crucial because the best data—observations over the past century or so—show that the climate is sensitive to human activity. “Thresholds of irreversible change are out there—we don’t know where,” Schneider notes. “What we do know is the more warming that’s out there, the more dangerous it gets.”

Wednesday 30 December 2009

Wednesday 23 December 2009

TckTckTck is a project of the the Global Campaign for Climate Action (GCCA

TckTckTck is a project of the the Global Campaign for Climate Action (GCCA), a bold, new initiative involving a growing number of national and global organizations in support of a single goal: to mobilize civil society and to galvanize public opinion in support of transformational change and rapid action to save the planet from dangerous levels of climate change.

organizations in support of a single goal: to mobilize civil society and to galvanize public opinion in support of transformational change and rapid action to save the planet from dangerous levels of climate change.

organizations in support of a single goal: to mobilize civil society and to galvanize public opinion in support of transformational change and rapid action to save the planet from dangerous levels of climate change.

organizations in support of a single goal: to mobilize civil society and to galvanize public opinion in support of transformational change and rapid action to save the planet from dangerous levels of climate change.

Barack Obama denies accusations that he 'crashed' secret Chinese climate change talks

Barack Obama denies accusations that he 'crashed' secret Chinese climate change talks

Senior US officials insist that President Barack Obama did not "crash" a secret Chinese meeting in the final dramatic hours of the Copenhagen climate change talks.

By Philip Sherwell in New York

Published: 7:22PM GMT 19 Dec 2009

They portrayed the President as pulling negotiations back from the brink of collapse on a day that veered between chaos and farce.

Aides said that by standing up to the Chinese on the make-and-break issue of transparency, he helped force a deal, however flimsy.

The President was desperate not to return to Washington empty-handed after his risky one-day dash to Denmark.

But his aides were forced to deny that Mr Obama "crashed" a meeting of the Chinese, Indian, South African and Brazilian leaders when he walked in unexpectedly on the gathering.

The US delegation was caught unawares by the session taking place behind its back involving the Chinese and their allies. Officials acknowledged that they had been frantically trying to keep track of other presidents and premiers.

Mr Obama thought he was on his way to a one-to-one meeting with Wen Jiabao, the Chinese premier, who had earlier snubbed him by skipping a session of world leaders.

But just before he entered the room, he was told that the other three leaders there too. "Good," he told aides and strode in with the words "Are you ready for me?" The Americans were particularly taken aback by the presence of Manmohan, the Indian premier, as they were told he had already headed to the airport.

"I think there was no doubt there was some surprise that we were going to join the bigger meeting," said a top Obama aide.

It was during the 80-minute meeting with the other four that the final details were hammered out.

Earlier in the day, at a one-to-one with Mr Wen, Obama aides said the president pushed the Chinese premier "hard" on transparency language. Mr Wen apparently took offence because when world leaders gathered later, he was notably absent. Beijing was instead represented by the climate change ambassador in the ministry of foreign affairs.

A senior US official said: "The President said to staff, I don't want to mess around with this anymore, I want to just talk with Premier Wen".

But the Americans were told that Mr Wen had left for his hotel and Mr Singh had already headed to the airport. The day meanwhile seemed destined for deadlock Mr Obama returned to the meeting with Gordon Brown and other European leaders.

Obama aides said that he courted support from the others present for pushing ahead with a deal, even without the backing of China and possibly India, South Africa and Brazil which shared some of Beijing's concerns.

The White House argued that it was this approach that created the leverage that persuaded the four to have "make one more run at this" "The senior official said: "I think that's why people stowed their luggage in their overhead bins and decided to come back [from the airport] to the negotiating table."

Without even having time to sign the agreement, the president had to dash to the airport to fly home before a winter blizzard slammed the East coast.

By the time he woke up in a snowbound Washington, the so-called "Copenhagen Accord" that he had brokered the previous evening was already unraveling.

Negotiators at the talks gave the deal only the most tepid thumbs-up.

They chose to "take note" of the agreement but failed to adopt it as an official decision of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change.

Speaking at the White House on Saturday, Mr Obama called the agreement an "important breakthrough that lays the foundation" for further progress in years to come. "We know it's not enough," he said. "We have a long way to go and I want America to continue to lead on this journey."

The president had already acknowledged the limitations of the "deal" when he was asked how confident he felt about securing a legally-binding agreement at next year's climate change summit in Mexico City.

"I think it is going to be very hard and it's going to take some time," he said after a day of drama that bordered on farce. He made clear that the ultimate goal was to "press ahead with something more binding".

But the agreement secured by Mr Obama lost wording from earlier drafts that calling for a binding accord "as soon as possible", and no later than at November's meeting in Mexico. Instead, the final version stated only that the agreement should be reviewed and put in place by 2015.

Mr Obama's aspiration to lead the world on climate change has been seriously undermined by the failure of the US Congress to reach agreement on the issue.

Senator John Kerry, lead author of the Senate's stalled climate change bill, expressed hope that the agreement would give fresh impetus for legislation early next year.

"This can be a catalysing moment," he said on Friday. "President Obama's hands-on engagement broke through the bickering and sets the stage for a final deal and for Senate passage this spring of major legislation at home."

But the accord set no target for concluding a binding international treaty, leaving the implementation of its provisions uncertain and fuelling criticism that it was more of a sham than a breakthrough.

It is expected to face several months, very possibly years, of follow-up negotiations before any internationally enforceable agreement can be reached.

Also dropped from earlier drafts was a collective agreement among nations to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 50 percent by 2050.

Nonetheless, some US environmental groups gave a cautious nod of approval.

"The world's nations have come together and concluded a historic - if incomplete - agreement to begin tackling global warming," Carl Pope, executive director of the Sierra Club, said on Friday. "Tonight's announcement is but a first step and much work remains to be done in the days and months ahead in order to seal a final international climate deal that is fair, binding and ambitious. It is imperative that negotiations resume as soon as possible."

But other US environmentalists were scathing of the president. Mr Obama may become known as "the man who killed Copenhagen," said Greenpeace US head Phil Radford.

Senior US officials insist that President Barack Obama did not "crash" a secret Chinese meeting in the final dramatic hours of the Copenhagen climate change talks.

By Philip Sherwell in New York

Published: 7:22PM GMT 19 Dec 2009

They portrayed the President as pulling negotiations back from the brink of collapse on a day that veered between chaos and farce.

Aides said that by standing up to the Chinese on the make-and-break issue of transparency, he helped force a deal, however flimsy.

The President was desperate not to return to Washington empty-handed after his risky one-day dash to Denmark.

But his aides were forced to deny that Mr Obama "crashed" a meeting of the Chinese, Indian, South African and Brazilian leaders when he walked in unexpectedly on the gathering.

The US delegation was caught unawares by the session taking place behind its back involving the Chinese and their allies. Officials acknowledged that they had been frantically trying to keep track of other presidents and premiers.

Mr Obama thought he was on his way to a one-to-one meeting with Wen Jiabao, the Chinese premier, who had earlier snubbed him by skipping a session of world leaders.

But just before he entered the room, he was told that the other three leaders there too. "Good," he told aides and strode in with the words "Are you ready for me?" The Americans were particularly taken aback by the presence of Manmohan, the Indian premier, as they were told he had already headed to the airport.

"I think there was no doubt there was some surprise that we were going to join the bigger meeting," said a top Obama aide.

It was during the 80-minute meeting with the other four that the final details were hammered out.

Earlier in the day, at a one-to-one with Mr Wen, Obama aides said the president pushed the Chinese premier "hard" on transparency language. Mr Wen apparently took offence because when world leaders gathered later, he was notably absent. Beijing was instead represented by the climate change ambassador in the ministry of foreign affairs.

A senior US official said: "The President said to staff, I don't want to mess around with this anymore, I want to just talk with Premier Wen".

But the Americans were told that Mr Wen had left for his hotel and Mr Singh had already headed to the airport. The day meanwhile seemed destined for deadlock Mr Obama returned to the meeting with Gordon Brown and other European leaders.

Obama aides said that he courted support from the others present for pushing ahead with a deal, even without the backing of China and possibly India, South Africa and Brazil which shared some of Beijing's concerns.

The White House argued that it was this approach that created the leverage that persuaded the four to have "make one more run at this" "The senior official said: "I think that's why people stowed their luggage in their overhead bins and decided to come back [from the airport] to the negotiating table."

Without even having time to sign the agreement, the president had to dash to the airport to fly home before a winter blizzard slammed the East coast.

By the time he woke up in a snowbound Washington, the so-called "Copenhagen Accord" that he had brokered the previous evening was already unraveling.

Negotiators at the talks gave the deal only the most tepid thumbs-up.

They chose to "take note" of the agreement but failed to adopt it as an official decision of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change.

Speaking at the White House on Saturday, Mr Obama called the agreement an "important breakthrough that lays the foundation" for further progress in years to come. "We know it's not enough," he said. "We have a long way to go and I want America to continue to lead on this journey."

The president had already acknowledged the limitations of the "deal" when he was asked how confident he felt about securing a legally-binding agreement at next year's climate change summit in Mexico City.

"I think it is going to be very hard and it's going to take some time," he said after a day of drama that bordered on farce. He made clear that the ultimate goal was to "press ahead with something more binding".

But the agreement secured by Mr Obama lost wording from earlier drafts that calling for a binding accord "as soon as possible", and no later than at November's meeting in Mexico. Instead, the final version stated only that the agreement should be reviewed and put in place by 2015.

Mr Obama's aspiration to lead the world on climate change has been seriously undermined by the failure of the US Congress to reach agreement on the issue.

Senator John Kerry, lead author of the Senate's stalled climate change bill, expressed hope that the agreement would give fresh impetus for legislation early next year.

"This can be a catalysing moment," he said on Friday. "President Obama's hands-on engagement broke through the bickering and sets the stage for a final deal and for Senate passage this spring of major legislation at home."

But the accord set no target for concluding a binding international treaty, leaving the implementation of its provisions uncertain and fuelling criticism that it was more of a sham than a breakthrough.

It is expected to face several months, very possibly years, of follow-up negotiations before any internationally enforceable agreement can be reached.

Also dropped from earlier drafts was a collective agreement among nations to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 50 percent by 2050.

Nonetheless, some US environmental groups gave a cautious nod of approval.

"The world's nations have come together and concluded a historic - if incomplete - agreement to begin tackling global warming," Carl Pope, executive director of the Sierra Club, said on Friday. "Tonight's announcement is but a first step and much work remains to be done in the days and months ahead in order to seal a final international climate deal that is fair, binding and ambitious. It is imperative that negotiations resume as soon as possible."

But other US environmentalists were scathing of the president. Mr Obama may become known as "the man who killed Copenhagen," said Greenpeace US head Phil Radford.

And Bill McKibbon of the liberal climate change pressure group 350.org, said: "The president has wrecked the UN and he's wrecked the possibility of a tough plan to control global warming. It may get Obama a reputation as a tough American leader, but it's at the expense of everything progressives have held dear."

Ed Miliband: China tried to hijack Copenhagen climate deal

Climate secretary accuses China, Sudan, Bolivia and other leftwing Latin American countries of trying to hijack Copenhagen.

John Vidal, environment editor

guardian.co.uk, Sunday 20 December 2009 20.30 GMT

The climate secretary, Ed Miliband, today accuses China, Sudan, Bolivia and other leftwing Latin American countries of trying to hijack the UN climate summit and "hold the world to ransom" to prevent a deal being reached.

In an article in the Guardian, Miliband says the UK will make clear to those countries holding out against a binding legal treaty that "we will not allow them to block global progress".

"We cannot again allow negotiations on real points of substance to be hijacked in this way," he writes in the aftermath of the UN summit in Copenhagen, which climaxed with what was widely seen as a weak accord, with no binding emissions targets, despite an unprecedented meeting of leaders.

Only China is mentioned specifically in Miliband's article but aides tonight made it clear that he included Sudan, Venezuela, Bolivia, Nicaragua and Cuba, which also tried to resist a deal being signed.

But in what threatened to become an international incident, diplomats and environment groups hit back by saying Britain and other countries, including the US and Australia, had dictated the terms of the weak Copenhagen agreement, imposing it on the world's poor "at the peril of the millions of common masses".

Muhammed Chowdhury, a lead negotiator of G77 group of 132 developing countries and the 47 least developed countries, said: "The hopes of millions of people from Fiji to Grenada, Bangladesh to Barbados, Sudan to Somalia have been buried. The summit failed to deliver beyond taking note of a watered-down Copenhagen accord reached by some 25 friends of the Danish chair, head of states and governments. They dictated the terms at the peril of the common masses."

Developing countries were joined in their criticism of the developed nations by international environment groups.

Nnimmo Bassey, chair of Friends of the Earth International, said: "Instead of committing to deep cuts in emissions and putting new, public money on the table to help solve the climate crisis, rich countries have bullied developing nations to accept far less.

"Those most responsible for putting the planet in this mess have not shown the guts required to fix it and have instead acted to protect short-term political interests.".

In a separate development, senior scientists said tonight that rich countries needed to put up three times as much money and cut emissions more if they were to avoid serious climate change.

Ed Miliband has pointed the finger at China over the outcome of the UN climate summit in Copenhagen. Photograph: Anja Niedringhaus/AP

John Vidal, environment editor

guardian.co.uk, Sunday 20 December 2009 20.30 GMT

The climate secretary, Ed Miliband, today accuses China, Sudan, Bolivia and other leftwing Latin American countries of trying to hijack the UN climate summit and "hold the world to ransom" to prevent a deal being reached.

In an article in the Guardian, Miliband says the UK will make clear to those countries holding out against a binding legal treaty that "we will not allow them to block global progress".

"We cannot again allow negotiations on real points of substance to be hijacked in this way," he writes in the aftermath of the UN summit in Copenhagen, which climaxed with what was widely seen as a weak accord, with no binding emissions targets, despite an unprecedented meeting of leaders.

Miliband said there must be "major reform" of the UN body overseeing the talks – the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) – and on the way negotiations are conducted. He is said to be outraged that UN procedure allowed a few countries to nearly block a deal.

The prime minister, Gordon Brown, will repeat some of the UK's accusations in a webcast tomorrow when he says: "Never again should we face the deadlock that threatened to pull down [those] talks. Never again should we let a global deal to move towards a greener future be held to ransom by only a handful of countries."

Only China is mentioned specifically in Miliband's article but aides tonight made it clear that he included Sudan, Venezuela, Bolivia, Nicaragua and Cuba, which also tried to resist a deal being signed.

But in what threatened to become an international incident, diplomats and environment groups hit back by saying Britain and other countries, including the US and Australia, had dictated the terms of the weak Copenhagen agreement, imposing it on the world's poor "at the peril of the millions of common masses".

Muhammed Chowdhury, a lead negotiator of G77 group of 132 developing countries and the 47 least developed countries, said: "The hopes of millions of people from Fiji to Grenada, Bangladesh to Barbados, Sudan to Somalia have been buried. The summit failed to deliver beyond taking note of a watered-down Copenhagen accord reached by some 25 friends of the Danish chair, head of states and governments. They dictated the terms at the peril of the common masses."

Developing countries were joined in their criticism of the developed nations by international environment groups.

Nnimmo Bassey, chair of Friends of the Earth International, said: "Instead of committing to deep cuts in emissions and putting new, public money on the table to help solve the climate crisis, rich countries have bullied developing nations to accept far less.

"Those most responsible for putting the planet in this mess have not shown the guts required to fix it and have instead acted to protect short-term political interests.".

In a separate development, senior scientists said tonight that rich countries needed to put up three times as much money and cut emissions more if they were to avoid serious climate change.

Professor Martin Parry of Imperial College London, a former chair of the UN's Nobel prize-winning Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, said: "Even if non-binding pledges made at Copenhagen are completely fulfilled, there is a 1.5C 'gap' leading to unavoided impacts. The funding for adaptation covers impacts up to about 1.5C, and the mitigation pledges to cut climate change down to 3C at most ... leaving 1.5C of impacts not avoided because of the failure of adaptation and mitigation to close the gap."

The UN climate chief, Yvo de Boer, said: "The opportunity to actually make it into the scientific window of opportunity is getting smaller and smaller."

Copenhagen 2009 - Comments from climate change experts

Copenhagen climate deal: Spectacular failure - or a few important steps?

We ask leading climate change experts for their assessment of the Copenhagen deal

Fuqiang Yang, director of global climate solutions, WWF International

The negotiations in Copenhagen ended without a fair, ambitious or legally binding treaty to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Despite this, what emerged was an agreement that will, at the very least, cut greenhouse gases, set up an emissions verification system, and reduce deforestation. Given the complexity of the issue, this represents a step forward.

I hasten to add that much of the hard work still lies ahead. The Copenhagen accord, the text that came out of the talks, leaves a long list of issues undecided. Among them are the emissions targets industrialised nations will accept, and how much climate finance they will offer.

The accord essentially allows countries to set their own greenhouse gas emissions reduction goals for 2020.

But I am optimistic, because the talks did achieve $100bn in aid from industrialised countries to poorer nations. China, as well, submitted to an emissions verification system under which all nations will report.

The accord also includes measures to help cut greenhouse gases and reduce deforestation, particularly in heavily forested developing nations such as Brazil and Indonesia.

These are big steps forward, and I think it is important to remember that there were achievements made in Copenhagen. There is still a great deal that needs to be done by China and all other signatories. Specific, binding targets are extremely important and need to be worked out. But we did see a move towards an agreement that could keep atmospheric Co2 levels from rising above dangerous levels.

John Prescott, climate change rapporteur for the Council of Europe

I've read a lot about so-called Brokenhagen and the failure to get a legally binding agreement. Frankly we were never going to get one, just as we didn't get one at Kyoto, when I was negotiating for the EU.

What you need is a statement of principle.

The details and targets to meet that principle will be settled at COP16 in Mexico in 12 months' time. Until then, countries must show, as Ban Ki-Moon said, greater ambition to turn their backs on the path of least resistance.

Many of the countries have set out their own carbon action plans by 2020. So let's see them put those plans into action and put those figures in the annexes to the Copenhagen accord. The rest of the world will follow.

Martin Rees, president of the Royal Society, master of Trinity College, professor of cosmology and astrophysics, university of Cambridge

Plainly the outcome of Copenhagen was less than many hoped – but perhaps not substantially less than could be realistically expected. The involvement of India and China was clearly going to be crucial.

We in the UK should surely acclaim the constructive and committed role played by our government, and by Gordon Brown and Ed Miliband in particular, both in the lead-up to Copenhagen and during the frustrating and exhasting negotiations last week.

Next year, one hopes the US internal debate will evolve further, so Obama feels able to play a less muted role. Let's hope also that negotiations within groups of nations are carried forward.

Bryony Worthington, climate campaigner with sandbag.org, who helped draft the UK climate change bill

Copenhagen was a spectacular failure on many levels. The UN process was stretched to breaking-point, with no consensus on any pressing issues.

The accord that was signed was clearly designed to meet the needs of the US, who always wanted a voluntary "pledge and review later" type agreement with minimum enforcement.

The sums of money agreed to help developing nations adapt to climate change are so low as to be insulting.

The future of the major mechanism driving private capital into solutions, the carbon market, has been left with a question mark over its future, and the long-anticipated agreement on stopping deforestation lacked clarity.

What happens next? The most honest answer would be to accept that under the current arrangements consensus will not be reached.

We have to focus on domestic action in big fossil-fuelled economies: the US, China, and Europe. All three have made pledges about their intentions to act – each has the opportunity to introduce policies which will create huge markets in climate solutions. If they lead, these solutions will become available for use in all parts of the world, with the costs of development having been born by those most able to pay.

That is our best hope.

Gavin Schmidt, climate scientist at Nasa and co-founder of the RealClimate blog

Look at the history of environment negotiations – take the ozone ones as the best example. People start off negotiating very hard and the first agreement does nothing but moderate the problem.

Carbon and climate change are much more complicated, and we're just getting to that 20-year mark now. Anyone expecting a definitive solution to the problem on timescales any shorter than that is extremely optimistic.

It's not an event, it's a process. I guarantee that the decisions we will be making in 2050 will not be the ones made in Copenhagen.

People are now seeing the problem for the challenge that it really is. But, in seeing that challenge, it makes the process – because that challenge is very large.

Kumi Naidoo, executive director, Greenpeace International

The outcome of the summit was not fair, ambitious or legally binding. This eluded world leaders because they put national economic self-interests, as well as those of climate polluting industries, before protecting the climate.

With each month of delay in getting a real climate deal, the chances of the world staying below a 2C rise slips further away, and the cost to this and the next generation in tackling climate change increases.

Vicky Pope, head of climate change advice at the Met Office

The accord is fairly weak, and we will only know how effective it will be when countries fill in the table that details their targets to reduce emissions (they have until the end of January to do so).

Only when we have those targets and we can add them up to see the scale of cuts will we be able to properly judge what has been achieved. It is a positive thing that finance is included, as that could help to make things happen.

Going forward, the first thing that needs to happen is that the table of targets needs to be filled in. Then the whole agreement needs to be made legally binding.

Nicholas Stern, chair, Grantham research institute on climate change and the environment, London School of Economics and Political Science

Dr Myles Allen, head of climate dynamics group in the atmospheric, oceanic and planetary physics department, University of Oxford

We ask leading climate change experts for their assessment of the Copenhagen deal

Fuqiang Yang, director of global climate solutions, WWF International

The negotiations in Copenhagen ended without a fair, ambitious or legally binding treaty to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Despite this, what emerged was an agreement that will, at the very least, cut greenhouse gases, set up an emissions verification system, and reduce deforestation. Given the complexity of the issue, this represents a step forward.

I hasten to add that much of the hard work still lies ahead. The Copenhagen accord, the text that came out of the talks, leaves a long list of issues undecided. Among them are the emissions targets industrialised nations will accept, and how much climate finance they will offer.

The accord essentially allows countries to set their own greenhouse gas emissions reduction goals for 2020.

But I am optimistic, because the talks did achieve $100bn in aid from industrialised countries to poorer nations. China, as well, submitted to an emissions verification system under which all nations will report.

The accord also includes measures to help cut greenhouse gases and reduce deforestation, particularly in heavily forested developing nations such as Brazil and Indonesia.

These are big steps forward, and I think it is important to remember that there were achievements made in Copenhagen. There is still a great deal that needs to be done by China and all other signatories. Specific, binding targets are extremely important and need to be worked out. But we did see a move towards an agreement that could keep atmospheric Co2 levels from rising above dangerous levels.

John Prescott, climate change rapporteur for the Council of Europe

I've read a lot about so-called Brokenhagen and the failure to get a legally binding agreement. Frankly we were never going to get one, just as we didn't get one at Kyoto, when I was negotiating for the EU.

What you need is a statement of principle.

At Copenhagen this was a final admission that we cannot let temperature rise 2C above pre-industrial levels.And to get approval from 192 countries on this principle is remarkable, considering Kyoto dealt with only 47 nations.

The details and targets to meet that principle will be settled at COP16 in Mexico in 12 months' time. Until then, countries must show, as Ban Ki-Moon said, greater ambition to turn their backs on the path of least resistance.

Many of the countries have set out their own carbon action plans by 2020. So let's see them put those plans into action and put those figures in the annexes to the Copenhagen accord. The rest of the world will follow.

Copenhagen's achievements are an acceptance of the science (contested at Kyoto), an admission there will be global emission cuts, and an acceptance that there will have to be verification.

Martin Rees, president of the Royal Society, master of Trinity College, professor of cosmology and astrophysics, university of Cambridge

Plainly the outcome of Copenhagen was less than many hoped – but perhaps not substantially less than could be realistically expected. The involvement of India and China was clearly going to be crucial.

But the grandstanding by particular nations (and the insistence by some on an unreasonable target of 1.5 degrees) was plainly unhelpful to the negotiations.

We in the UK should surely acclaim the constructive and committed role played by our government, and by Gordon Brown and Ed Miliband in particular, both in the lead-up to Copenhagen and during the frustrating and exhasting negotiations last week.

Next year, one hopes the US internal debate will evolve further, so Obama feels able to play a less muted role. Let's hope also that negotiations within groups of nations are carried forward.

There is more hope of something being agreed among a group of up to 20 key nations (provided the group covers developing and developed countries), which others then sign up to.

And to be positive, the Copenhagen meeting, circus though it was, carried the process forward. For instance, it stimulated pledges of funding from developed nations (albeit, not as firmly as might have been hoped) and made progress on forestry. And it maintained global long-term concerns about climate change on the international agenda.

Bryony Worthington, climate campaigner with sandbag.org, who helped draft the UK climate change bill

Copenhagen was a spectacular failure on many levels. The UN process was stretched to breaking-point, with no consensus on any pressing issues.

The accord that was signed was clearly designed to meet the needs of the US, who always wanted a voluntary "pledge and review later" type agreement with minimum enforcement.

The sums of money agreed to help developing nations adapt to climate change are so low as to be insulting.

The future of the major mechanism driving private capital into solutions, the carbon market, has been left with a question mark over its future, and the long-anticipated agreement on stopping deforestation lacked clarity.

What happens next? The most honest answer would be to accept that under the current arrangements consensus will not be reached.

We have to focus on domestic action in big fossil-fuelled economies: the US, China, and Europe. All three have made pledges about their intentions to act – each has the opportunity to introduce policies which will create huge markets in climate solutions. If they lead, these solutions will become available for use in all parts of the world, with the costs of development having been born by those most able to pay.

That is our best hope.

Gavin Schmidt, climate scientist at Nasa and co-founder of the RealClimate blog

Look at the history of environment negotiations – take the ozone ones as the best example. People start off negotiating very hard and the first agreement does nothing but moderate the problem.

While the Montreal protocol was ultimately a huge triumph, it made an infinitesimally small difference at first. It took them four amendments to get from reduction to a ban [on CFCs], a process of 20 years after science identified the problem.

Carbon and climate change are much more complicated, and we're just getting to that 20-year mark now. Anyone expecting a definitive solution to the problem on timescales any shorter than that is extremely optimistic.

It's not an event, it's a process. I guarantee that the decisions we will be making in 2050 will not be the ones made in Copenhagen.

Copenhagen did show some improvement in the process. People are now talking about changes in greenhouse gas emissions that are commensurate with the size of the problem. Before, they weren't.

People are now seeing the problem for the challenge that it really is. But, in seeing that challenge, it makes the process – because that challenge is very large.

Kumi Naidoo, executive director, Greenpeace International

The outcome of the summit was not fair, ambitious or legally binding. This eluded world leaders because they put national economic self-interests, as well as those of climate polluting industries, before protecting the climate.

Even if all countries reach their pledges, our planet will be propelled towards a 4C temperature rise, double what leaders say they must achieve. This will have devastating climate impacts, including crop failures and the disappearance of the Amazon rainforest and the Great Barrier Reef.

With each month of delay in getting a real climate deal, the chances of the world staying below a 2C rise slips further away, and the cost to this and the next generation in tackling climate change increases.

To avoid this, industrialised countries as a group – which bear historic responsibility for the problem – must make the largest emission cuts. They also need to provide at least $140bn a year to help developing countries.

The non-result from Copenhagen calls into question the ability of leaders to deliver what is needed. Citizens around the world will need to elect more ambitious leaders and embrace new, low impact technologies.

Vicky Pope, head of climate change advice at the Met Office

At previous meetings in the runup to Copenhagen, in Barcelona and elsewhere, there was talk about greenhouse gas targets for 2020 and 2050; it is disappointing that those have been lost, but it is good that everyone accepted the scientific reality that climate change is a problem and that we need to limit warming to 2C.

The accord is fairly weak, and we will only know how effective it will be when countries fill in the table that details their targets to reduce emissions (they have until the end of January to do so).

Only when we have those targets and we can add them up to see the scale of cuts will we be able to properly judge what has been achieved. It is a positive thing that finance is included, as that could help to make things happen.

Going forward, the first thing that needs to happen is that the table of targets needs to be filled in. Then the whole agreement needs to be made legally binding.

Nicholas Stern, chair, Grantham research institute on climate change and the environment, London School of Economics and Political Science

The Copenhagen meeting was a disappointment, primarily because it failed to set the basic targets for reducing global annual emissions of greenhouse gases from now up to 2050, and did not secure commitments from countries to meet these targets collectively.

Nevertheless, the road to Copenhagen and the summit itself generated commitments on emissions reductions from many countries, including, for the first time, from the world's two largest emitters, China and the US. The Copenhagen accord also did recognise that a rise in global average temperature should be limited to below 2C.

In addition, the prime minister of Ethiopia, Meles Zenawi, speaking for the African Union, put forward a very important proposal on financial support, much of which is reflected in the Copenhagen accord, including the creation of the Copenhagen green climate fund to administer funding for developing countries.

The current UN framework convention on climate change process has been found wanting over the past few weeks.

One potential way forward is for Mexico, as hosts of COP16 (the next full summit) in 2010, to convene a group of 20 representative nations, as Friends of the Chair, to work on a potential treaty and tackle the outstanding issues and building consensus around strong action. The group should start its work immediately.

Dr Myles Allen, head of climate dynamics group in the atmospheric, oceanic and planetary physics department, University of Oxford

On one level, it could be argued it is quite a good outcome.

There is a goal to limit global temperature rise to 2C and an acknowledgement that current commitments are not enough to meet that goal. It is good that China recognises the 2C goal and that emissions reductions are the way to go.

I am glad they did not make serious progress towards a legally binding treaty, because the current thinking that nationally negotiated emissions targets and a system of carbon trading will solve this problem is flawed. I'm very sceptical about that whole approach.

A legally binding regime based on that principle would lock us into that process, and it could take 20 or 30 years before it became sufficiently obvious it was not working. Once set up, there is enormous investment in a system like that and it becomes difficult to change. So something close to success in Copenhagen based on what the politicians were aiming for could have been counterproductive.

It's depressing that governments appear to have walked away from Copenhagen only to say they are going to spend the next year fighting for the legally binding treaty they wanted it to produce, rather than use the time to consider some radical alternatives.

One way we have suggested is to target producers rather than emitters. A mandatory requirement on fossil fuel companies to capture and store carbon emissions, to clean up after themselves, could solve a big part of the problem without complex international negotiations.

Tuesday 22 December 2009

How do I know China wrecked the Copenhagen deal? I was in the room

As recriminations fly post-Copenhagen, one writer offers a fly-on-the-wall account of how talks failed

Mark Lynas

guardian.co.uk, Tuesday 22 December 2009 19.54 GMT

Mark Lynas wrote Six Degrees: Our future on a hotter planet

And sure enough, the aid agencies, civil society movements and environmental groups all took the bait. The failure was "the inevitable result of rich countries refusing adequately and fairly to shoulder their overwhelming responsibility", said Christian Aid. "Rich countries have bullied developing nations," fumed Friends of the Earth International.

All very predictable, but the complete opposite of the truth. Even George Monbiot, writing in yesterday's Guardian, made the mistake of singly blaming Obama. But I saw Obama fighting desperately to salvage a deal, and the Chinese delegate saying "no", over and over again. Monbiot even approvingly quoted the Sudanese delegate Lumumba Di-Aping, who denounced the Copenhagen accord as "a suicide pact, an incineration pact, in order to maintain the economic dominance of a few countries".

Sudan behaves at the talks as a puppet of China; one of a number of countries that relieves the Chinese delegation of having to fight its battles in open sessions. It was a perfect stitch-up. China gutted the deal behind the scenes, and then left its proxies to savage it in public.

Here's what actually went on late last Friday night, as heads of state from two dozen countries met behind closed doors. Obama was at the table for several hours, sitting between Gordon Brown and the Ethiopian prime minister, Meles Zenawi. The Danish prime minister chaired, and on his right sat Ban Ki-moon, secretary-general of the UN. Probably only about 50 or 60 people, including the heads of state, were in the room. I was attached to one of the delegations, whose head of state was also present for most of the time.

What I saw was profoundly shocking. The Chinese premier, Wen Jinbao, did not deign to attend the meetings personally, instead sending a second-tier official in the country's foreign ministry to sit opposite Obama himself. The diplomatic snub was obvious and brutal, as was the practical implication: several times during the session, the world's most powerful heads of state were forced to wait around as the Chinese delegate went off to make telephone calls to his "superiors".

Shifting the blame

Australia's prime minister, Kevin Rudd, was annoyed enough to bang his microphone. Brazil's representative too pointed out the illogicality of China's position. Why should rich countries not announce even this unilateral cut? The Chinese delegate said no, and I watched, aghast, as Merkel threw up her hands in despair and conceded the point. Now we know why – because China bet, correctly, that Obama would get the blame for the Copenhagen accord's lack of ambition.

Strong position

So how did China manage to pull off this coup? First, it was in an extremely strong negotiating position. China didn't need a deal. As one developing country foreign minister said to me: "The Athenians had nothing to offer to the Spartans." On the other hand, western leaders in particular – but also presidents Lula of Brazil, Zuma of South Africa, Calderón of Mexico and many others – were desperate for a positive outcome. Obama needed a strong deal perhaps more than anyone. The US had confirmed the offer of $100bn to developing countries for adaptation, put serious cuts on the table for the first time (17% below 2005 levels by 2020), and was obviously prepared to up its offer.

Above all, Obama needed to be able to demonstrate to the Senate that he could deliver China in any global climate regulation framework, so conservative senators could not argue that US carbon cuts would further advantage Chinese industry. With midterm elections looming, Obama and his staff also knew that Copenhagen would be probably their only opportunity to go to climate change talks with a strong mandate. This further strengthened China's negotiating hand, as did the complete lack of civil society political pressure on either China or India. Campaign groups never blame developing countries for failure; this is an iron rule that is never broken. The Indians, in particular, have become past masters at co-opting the language of equity ("equal rights to the atmosphere") in the service of planetary suicide – and leftish campaigners and commentators are hoist with their own petard.

China's game

This does not mean China is not serious about global warming. It is strong in both the wind and solar industries. But China's growth, and growing global political and economic dominance, is based largely on cheap coal. China knows it is becoming an uncontested superpower; indeed its newfound muscular confidence was on striking display in Copenhagen. Its coal-based economy doubles every decade, and its power increases commensurately. Its leadership will not alter this magic formula unless they absolutely have to.

Copenhagen was much worse than just another bad deal, because it illustrated a profound shift in global geopolitics. This is fast becoming China's century, yet its leadership has displayed that multilateral environmental governance is not only not a priority, but is viewed as a hindrance to the new superpower's freedom of action.

Mark Lynas

guardian.co.uk, Tuesday 22 December 2009 19.54 GMT

Mark Lynas wrote Six Degrees: Our future on a hotter planet

Copenhagen was a disaster. That much is agreed. But the truth about what actually happened is in danger of being lost amid the spin and inevitable mutual recriminations. The truth is this: China wrecked the talks, intentionally humiliated Barack Obama, and insisted on an awful "deal" so western leaders would walk away carrying the blame. How do I know this? Because I was in the room and saw it happen.

China's strategy was simple: block the open negotiations for two weeks, and then ensure that the closed-door deal made it look as if the west had failed the world's poor once again.

And sure enough, the aid agencies, civil society movements and environmental groups all took the bait. The failure was "the inevitable result of rich countries refusing adequately and fairly to shoulder their overwhelming responsibility", said Christian Aid. "Rich countries have bullied developing nations," fumed Friends of the Earth International.

All very predictable, but the complete opposite of the truth. Even George Monbiot, writing in yesterday's Guardian, made the mistake of singly blaming Obama. But I saw Obama fighting desperately to salvage a deal, and the Chinese delegate saying "no", over and over again. Monbiot even approvingly quoted the Sudanese delegate Lumumba Di-Aping, who denounced the Copenhagen accord as "a suicide pact, an incineration pact, in order to maintain the economic dominance of a few countries".

Sudan behaves at the talks as a puppet of China; one of a number of countries that relieves the Chinese delegation of having to fight its battles in open sessions. It was a perfect stitch-up. China gutted the deal behind the scenes, and then left its proxies to savage it in public.

Here's what actually went on late last Friday night, as heads of state from two dozen countries met behind closed doors. Obama was at the table for several hours, sitting between Gordon Brown and the Ethiopian prime minister, Meles Zenawi. The Danish prime minister chaired, and on his right sat Ban Ki-moon, secretary-general of the UN. Probably only about 50 or 60 people, including the heads of state, were in the room. I was attached to one of the delegations, whose head of state was also present for most of the time.

What I saw was profoundly shocking. The Chinese premier, Wen Jinbao, did not deign to attend the meetings personally, instead sending a second-tier official in the country's foreign ministry to sit opposite Obama himself. The diplomatic snub was obvious and brutal, as was the practical implication: several times during the session, the world's most powerful heads of state were forced to wait around as the Chinese delegate went off to make telephone calls to his "superiors".

Shifting the blame

To those who would blame Obama and rich countries in general, know this: it was China's representative who insisted that industrialised country targets, previously agreed as an 80% cut by 2050, be taken out of the deal. "Why can't we even mention our own targets?" demanded a furious Angela Merkel.

Australia's prime minister, Kevin Rudd, was annoyed enough to bang his microphone. Brazil's representative too pointed out the illogicality of China's position. Why should rich countries not announce even this unilateral cut? The Chinese delegate said no, and I watched, aghast, as Merkel threw up her hands in despair and conceded the point. Now we know why – because China bet, correctly, that Obama would get the blame for the Copenhagen accord's lack of ambition.

China, backed at times by India, then proceeded to take out all the numbers that mattered. A 2020 peaking year in global emissions, essential to restrain temperatures to 2C, was removed and replaced by woolly language suggesting that emissions should peak "as soon as possible". The long-term target, of global 50% cuts by 2050, was also excised. No one else, perhaps with the exceptions of India and Saudi Arabia, wanted this to happen. I am certain that had the Chinese not been in the room, we would have left Copenhagen with a deal that had environmentalists popping champagne corks popping in every corner of the world.

Strong position

So how did China manage to pull off this coup? First, it was in an extremely strong negotiating position. China didn't need a deal. As one developing country foreign minister said to me: "The Athenians had nothing to offer to the Spartans." On the other hand, western leaders in particular – but also presidents Lula of Brazil, Zuma of South Africa, Calderón of Mexico and many others – were desperate for a positive outcome. Obama needed a strong deal perhaps more than anyone. The US had confirmed the offer of $100bn to developing countries for adaptation, put serious cuts on the table for the first time (17% below 2005 levels by 2020), and was obviously prepared to up its offer.

Above all, Obama needed to be able to demonstrate to the Senate that he could deliver China in any global climate regulation framework, so conservative senators could not argue that US carbon cuts would further advantage Chinese industry. With midterm elections looming, Obama and his staff also knew that Copenhagen would be probably their only opportunity to go to climate change talks with a strong mandate. This further strengthened China's negotiating hand, as did the complete lack of civil society political pressure on either China or India. Campaign groups never blame developing countries for failure; this is an iron rule that is never broken. The Indians, in particular, have become past masters at co-opting the language of equity ("equal rights to the atmosphere") in the service of planetary suicide – and leftish campaigners and commentators are hoist with their own petard.

With the deal gutted, the heads of state session concluded with a final battle as the Chinese delegate insisted on removing the 1.5C target so beloved of the small island states and low-lying nations who have most to lose from rising seas. President Nasheed of the Maldives, supported by Brown, fought valiantly to save this crucial number. "How can you ask my country to go extinct?" demanded Nasheed. The Chinese delegate feigned great offence – and the number stayed, but surrounded by language which makes it all but meaningless. The deed was done.

China's game

All this raises the question: what is China's game? Why did China, in the words of a UK-based analyst who also spent hours in heads of state meetings, "not only reject targets for itself, but also refuse to allow any other country to take on binding targets?" The analyst, who has attended climate conferences for more than 15 years, concludes that China wants to weaken the climate regulation regime now "in order to avoid the risk that it might be called on to be more ambitious in a few years' time".

This does not mean China is not serious about global warming. It is strong in both the wind and solar industries. But China's growth, and growing global political and economic dominance, is based largely on cheap coal. China knows it is becoming an uncontested superpower; indeed its newfound muscular confidence was on striking display in Copenhagen. Its coal-based economy doubles every decade, and its power increases commensurately. Its leadership will not alter this magic formula unless they absolutely have to.

Copenhagen was much worse than just another bad deal, because it illustrated a profound shift in global geopolitics. This is fast becoming China's century, yet its leadership has displayed that multilateral environmental governance is not only not a priority, but is viewed as a hindrance to the new superpower's freedom of action.

I left Copenhagen more despondent than I have felt in a long time. After all the hope and all the hype, the mobilisation of thousands, a wave of optimism crashed against the rock of global power politics, fell back, and drained away.

Efforts to secure a legally-binding climate change deal failed last week because talks were ''held to ransom'' by a small number of countries, Gordon Brown has said.

Efforts to secure a legally-binding climate change deal failed last week because talks were ''held to ransom'' by a small number of countries, Gordon Brown has said.

As the UK pointed the finger of blame at China for blocking progress at the UN-sponsored summit in Copenhagen, he called for a new international body to take charge of future negotiations.

Days of chaotic talks between more than 190 countries produced an accord that average world temperature rises should not exceed 2C but without commitments to emissions cuts to achieve it.

There was also agreement on a fund, to reach 100 billion US dollars by 2020, to help poorer countries deal with global warming, but no precise detail on where the money will come from.

The Prime Minister, who spent four days in the Danish capital trying to secure a stronger deal, admitted that he feared the talks could collapse without even those advances.

And, in a webcast to be posted on the Number 10 site, he pledged to continue pressing for a binding deal and demanded action to ensure a minority of countries could not block future efforts.

''The talks in Copenhagen were not easy. and, as they reached conclusion, I did fear the process would collapse and we would have no deal at all,'' he said.

''Yet, through strength of common purpose, we were able finally to break the deadlock and - in a breakthrough never seen on this scale before - secure agreement from the international community.''

Calling on the world to ''learn lessons'' from last week's frantic scenes, he said: ''Never again should we face the deadlock that threatened to pull down those talks; never again should we let a global deal to move towards a greener future be held to ransom by only a handful of countries.

''One of the frustrations for me was the lack of a global body with the sole responsibility for environmental stewardship.

''I believe that in 2010 we will need to look at reforming our international institutions to meet the common challenges we face as a global community.''

Ed Miliband, the Environment Secretary, earlier accused China of ''hijacking'' the Copenhagen summit and said Beijing had ''vetoed'' moves to give legal force to the accord and prevented agreement on 50 per cent global reductions in greenhouse emissions - 80% in the most developed countries - by 2050.

''We did not get an agreement on 50 per cent reductions in global emissions by 2050 or on 80 per cent reductions by developed countries. Both were vetoed by China, despite the support of a coalition of developed and the vast majority of developing countries,'' he wrote in The Guardian.

''Together we will make clear to those countries holding out against a binding legal treaty that we will not allow them to block global progress,'' he said.

''The last two weeks at times have presented a farcical picture to the public. We cannot again allow negotiations on real points of substance to be hijacked in this way.

''We will need to have major reform of the UN body overseeing the negotiations and of the way the negotiations are conducted.''

Despite his frustrations, Mr Miliband insisted that Britain was right to sign the limited Copenhagen accord, which he said delivered ''real outcomes'' on temperature rises and finance.

''We should take heart from the achievements and step up our efforts,'' he said.

''The road from Copenhagen will have as many obstacles as the road to it. But this year has proved what can be done, as well as the scale of the challenge we face.''

A brief history of climate change

BBC News environment correspondent Richard Black traces key milestones, scientific discoveries, technical innovations and political action.

The Newcomen Engine foreshadowed industrial scale use of coal |

1712 - British ironmonger Thomas Newcomen invents the first widely used steam engine, paving the way for the Industrial Revolution and industrial scale use of coal.

1800 - world population reaches one billion.

1824 - French physicist Joseph Fourier describes the Earth's natural "greenhouse effect". He writes: "The temperature [of the Earth] can be augmented by the interposition of the atmosphere, because heat in the state of light finds less resistance in penetrating the air, than in re-passing into the air when converted into non-luminous heat."

1861 - Irish physicist John Tyndall shows that water vapour and certain other gases create the greenhouse effect. "This aqueous vapour is a blanket more necessary to the vegetable life of England than clothing is to man," he concludes. More than a century later, he is honoured by having a prominent UK climate research organisation - the Tyndall Centre - named after him.

1886 - Karl Benz unveils the Motorwagen, often regarded as the first true automobile.

1896 - Swedish chemist Svante Arrhenius concludes that industrial-age coal burning will enhance the natural greenhouse effect. He suggests this might be beneficial for future generations. His conclusions on the likely size of the "man-made greenhouse" are in the same ballpark - a few degrees Celsius for a doubling of CO2 - as modern-day climate models.

Svante Arrhenius unlocked the man-made greenhouse a century ago |

1900 - another Swede, Knut Angstrom, discovers that even at the tiny concentrations found in the atmosphere, CO2 strongly absorbs parts of the infrared spectrum. Although he does not realise the significance, Angstrom has shown that a trace gas can produce greenhouse warming.

1927 - carbon emissions from fossil fuel burning and industry reach one billion tonnes per year.

1930 - human population reaches two billion.

1938 - using records from 147 weather stations around the world, British engineer Guy Callendar shows that temperatures had risen over the previous century. He also shows that CO2 concentrations had increased over the same period, and suggests this caused the warming. The "Callendar effect" is widely dismissed by meteorologists.

1955 - using a new generation of equipment including early computers, US researcher Gilbert Plass analyses in detail the infrared absorption of various gases. He concludes that doubling CO2 concentrations would increase temperatures by 3-4C.

1957 - US oceanographer Roger Revelle and chemist Hans Suess show that seawater will not absorb all the additional CO2 entering the atmosphere, as many had assumed. Revelle writes: "Human beings are now carrying out a large scale geophysical experiment..."

1958 - using equipment he had developed himself, Charles David (Dave) Keeling begins systematic measurements of atmospheric CO2 at Mauna Loa in Hawaii and in Antarctica. Within four years, the project - which continues today - provides the first unequivocal proof that CO2 concentrations are rising.

Margaret Thatcher |

1960 - human population reaches three billion.

1965 - a US President's Advisory Committee panel warns that the greenhouse effect is a matter of "real concern".

1972 - first UN environment conference, in Stockholm. Climate change hardly registers on the agenda, which centres on issues such as chemical pollution, atomic bomb testing and whaling. The United Nations Environment Programme (Unep) is formed as a result.

1975 - human population reaches four billion.

1975 - US scientist Wallace Broecker puts the term "global warming" into the public domain in the title of a scientific paper.

1987 - human population reaches five billion

1987 - Montreal Protocol agreed, restricting chemicals that damage the ozone layer. Although not established with climate change in mind, it has had a greater impact on greenhouse gas emissions than the Kyoto Protocol.

1988 - Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) formed to collate and assess evidence on climate change.

1989 - UK Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher - possessor of a chemistry degree - warns in a speech to the UN that "We are seeing a vast increase in the amount of carbon dioxide reaching the atmosphere... The result is that change in future is likely to be more fundamental and more widespread than anything we have known hitherto." She calls for a global treaty on climate change.

1989 - carbon emissions from fossil fuel burning and industry reach six billion tonnes per year.

The CO2 concentration, as measured at Mauna Loa, has risen steadily |

1990 - IPCC produces First Assessment Report. It concludes that temperatures have risen by 0.3-0.6C over the last century, that humanity's emissions are adding to the atmosphere's natural complement of greenhouse gases, and that the addition would be expected to result in warming.

1992 - at the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro, governments agree the United Framework Convention on Climate Change. Its key objective is "stabilization of greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere at a level that would prevent dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system". Developed countries agree to return their emissions to 1990 levels.

1995 - IPCC Second Assessment Report concludes that the balance of evidence suggests "a discernible human influence" on the Earth's climate. This has been called the first definitive statement that humans are responsible for climate change.

1997 - Kyoto Protocol agreed. Developed nations pledge to reduce emissions by an average of 5% by the period 2008-2012, with wide variations on targets for individual countries. US Senate immediately declares it will not ratify the treaty.

1998 - strong El Nino conditions combine with global warming to produce the warmest year on record. The average global temperature reached 0.52C above the mean for the period 1961-1990 (a commonly-used baseline).

1998 - publication of the controversial "hockey stick" graph indicating that modern-day temperature rise in the northern hemisphere is unusual compared with the last 1,000 years. The work would later be the subject of two enquiries instigated by the US Congress.

Rajendra Pachauri's IPCC netted the Nobel Peace Prize in 2007 |

1999 - human population reaches six billion.

2001 - President George W Bush removes the US from the Kyoto process.

2001 - IPCC Third Assessment Report finds "new and stronger evidence" that humanity's emissions of greenhouse gases are the main cause of the warming seen in the second half of the 20th Century.

2005 - the Kyoto Protocol becomes international law for those countries still inside it.

2005 - UK Prime Minister Tony Blair selects climate change as a priority for his terms as chair of the G8 and president of the EU.

2006 - the Stern Review concludes that climate change could damage global GDP by up to 20% if left unchecked - but curbing it would cost about 1% of global GDP.

2006 - carbon emissions from fossil fuel burning and industry reach eight billion tonnes per year.

2007 - the IPCC's Fourth Assessment Report concludes it is more than 90% likely that humanity's emissions of greenhouse gases are responsible for modern-day climate change.

2007 - the IPCC and former US vice-president Al Gore receive the Nobel Peace Prize "for their efforts to build up and disseminate greater knowledge about man-made climate change, and to lay the foundations for the measures that are needed to counteract such change".

2007 - at UN negotiations in Bali, governments agree the two-year "Bali roadmap" aimed at hammering out a new global treaty by the end of 2009.

2008 - half a century after beginning observations at Mauna Loa, the Keeling project shows that CO2 concentrations have risen from 315 parts per million (ppm) in 1958 to 380ppm in 2008.

2008 - two months before taking office, incoming US president Barack Obama pledges to "engage vigorously" with the rest of the world on climate change.

2009 - China overtakes the US as the world's biggest greenhouse gas emitter - although the US remains well ahead on a per-capita basis.

2009 - 192 governments convene for the UN climate summit in Copenhagen.

A journey through the Earth's climate history

The pictures and commentary below are taken from the BBCs Roger Black 3 minute lecture.

Now that world leaders have met in Copenhagen to discuss climate change - how did the Earth's climate arrive at its current state and how do scientists delve into the secrets of our planet's past?

The layers of ice laid down each year in Antarctica and Greenland store a record of the Earth's climate. Bubbles of air trapped in the ice as it froze can be analysed to give details on temperature at the time it froze, and on atmospheric concentrations of gases.

The oldest ice core so far extracted belongs to the European Project for Ice Coring in Antarctica (Epica). It allows scientists to look back 800,000 years.

Over time, the Earth's orbit around the Sun varies slightly. This changes the amount of solar energy reaching the Earth's surface, alternately warming and cooling the planet's surface.

In a warming phase, greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide are released and amplify the warming - increasing the natural greenhouse effect.

They are stored again when an ice age starts.

So over this period, we see temperature and carbon dioxide concentrations changing in step, in cycles lasting about 100,000 years.

About 10,000 years ago, the Earth emerged from its most recent ice age. Agriculture developed, and the extra food supported a growing global population.

The last 1,000 years saw development of international trade - and eventually, in the 1700s, the birth of the Industrial Revolution.

This ran largely on coal and later, oil.

The human population was also growing, reaching one billion around the start of the 19th Century.

By this time, a growing network of weather stations was taking daily measurements of temperature, a record that increases in precision as time goes on.

In the 20th Century, fuel use, industry, land clearance and agriculture all increased atmospheric concentrations of CO2 and other greenhouse gases.

The temperature curve for the last 100 years shows two distinct periods of warming with an intervening period of cooling around 1940, probably caused by increased industrial emissions of aerosols, tiny particles that reflect sunlight.

In the second half of the century, highly accurate measurements, taken initially in Hawaii and Antarctica, proved that carbon dioxide concentrations were steadily rising in a regular manner. Other greenhouse gases such as methane showed similar trends.

Rapid expansion of the global economy.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) concludes it is more than 90% probable that the warming seen in the second half of the 20th Century is mainly driven by human emissions of greenhouse gases.

Unless temperatures are constrained, there will be severe consequences in some parts of the world.

Sources and resources

DATA DOWNLOAD Download the climate data below |

The data, for the animation , on temperature and carbon dioxide for the 800,000 year time period is taken from the European Project for Ice Coring in Antarctica, Epica.The data can be downloaded using the link on the right and was complied by Dr Robert Mulvaney of the British Antarctic Survey.

For the time period covering the last 1,500 years the CO2 record is from the Law Dome ice core, again in Antarctica. McFarling Meure et al, 2006 is the source. For the past 60 or so years the CO2 source is the readings taken at Mauna Loa by the NOAA.

Temperature for the last 1,500 years is taken from Mann, M.E., Zhang, Z., Hughes, M.K., Bradley, R.S., Miller, S.K., Rutherford, S.,Proxy-Based Reconstructions of Hemispheric and Global Surface Temperature Variations over the Past Two Millennia, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., 105, 13252-13257, 2008.

For the final time period covered, the temperature data is sourced to the Met Office Hadley Centre and to the Climatic Research Unit at the University of East Anglia.

The illustration showing the extent of ice cover over North America 20,000 years ago is credited to Ehlers and Gibbard.

Population figures are sourced to the US Census Bureau and the UN.Figures on per capita GDP are from Angus Maddison.

More information on the Earth's past climate can be found at the NOAA's palaeoclimatology page and from the IPCC's 2007 report.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)