Planet earth viewed from space. Photograph: Corbis

If you shout "fire" in a crowded theatre, when there is none, you understand that you might be arrested for irresponsible behaviour and breach of the peace. But from today, I smell smoke, I see flames and I think it is time to shout. I don't want you to panic, but I do think it would be a good idea to form an orderly queue to leave the building.

Because

in just 100 months' time, if we are lucky, and based on a quite conservative estimate, we could reach a tipping point for the beginnings of runaway climate change.

That said, among people working on global warming, there are countless models, scenarios, and different iterations of all those models and scenarios. So, let us be clear from the outset about exactly what we mean.

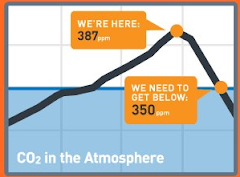

The concentration of carbon dioxide (CO2) in the atmosphere today, the most prevalent greenhouse gas, is the highest it has been for the past 650,000 years. In the space of just 250 years, as a result of the coal-fired Industrial Revolution, and changes to land use such as the growth of cities and the felling of forests, we have released, cumulatively, more than 1,800bn tonnes of CO2 into the atmosphere.

Currently, approximately 1,000 tonnes of CO2 are released into the Earth's atmosphere every second, due to human activity.

Greenhouse gases trap incoming solar radiation, warming the atmosphere. When these gases accumulate beyond a certain level - often termed a "tipping point" - global warming will accelerate, potentially beyond control.

Faced with circumstances that clearly threaten human civilisation, scientists at least have the sense of humour to term what drives this process as "positive feedback". But if translated into an office workplace environment, it's the sort of "positive feedback" from a manager that would run along the lines of: "You're fired, you were rubbish anyway, you have no future, your home has been demolished and I've killed your dog."

In climate change, a number of feedback loops amplify warming through physical processes that are either triggered by the initial warming itself, or the increase in greenhouse gases. One example is the melting of ice sheets. The loss of ice cover reduces the ability of the Earth's surface to reflect heat and, by revealing darker surfaces, increases the amount of heat absorbed. Other dynamics include the decreasing ability of oceans to absorb CO2 due to higher wind strengths linked to climate change. This has already been observed in the Southern Ocean and North Atlantic, increasing the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere, and adding to climate change.

Because of such self-reinforcing positive feedbacks (which, because of the accidental humour of science, we must remind ourselves are, in fact, negative),

once a critical greenhouse concentration threshold is passed, global warming will continue even if we stop releasing additional greenhouse gases into the atmosphere.

If that happens, the Earth's climate will shift into another, more volatile state, with different ocean circulation, wind and rainfall patterns. The implications of which, according to a growing litany of research, are potentially catastrophic for life on Earth. Such a change in the state of the climate system is often referred to as irreversible climate change.

So, how exactly do we arrive at the ticking clock of 100 months? It's possible to estimate the length of time it will take to reach a tipping point. To do so you combine current greenhouse gas concentrations with the best estimates for the rates at which emissions are growing, the maximum concentration of greenhouse gases allowable to forestall potentially irreversible changes to the climate system, and the effect of those environmental feedbacks. We followed the latest data and trends for carbon dioxide, then made allowances for all human interferences that influence temperatures, both those with warming and cooling effects. We followed the judgments of the mainstream climate science community, represented by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), on what it will take to retain a good chance of not crossing the critical threshold of the Earth's average surface temperature rising by 2C above pre-industrial levels. We were cautious in several ways, optimistic even, and perhaps too much so. A rise of 2C may mask big problems that begin at a lower level of warming. For example, collapse of the Greenland ice sheet is more than likely to be triggered by a local warming of 2.7C, which could correspond to a global mean temperature increase of 2C or less. The disintegration of the Greenland ice sheet could correspond to a sea-level rise of up to 7 metres.

In arriving at our timescale, we also used the lower end of threats in assessing the impact of vanishing ice cover and other carbon-cycle feedbacks (those wanting more can download a note on method from onehundredmonths.org). But the result is worrying enough.

We found that, given all of the above, 100 months from today we will reach a concentration of greenhouse gases at which it is no longer "likely" that we will stay below the 2C temperature rise threshold. "Likely" in this context refers to the definition of risk used by the IPCC. But, even just before that point, there is still a one third chance of crossing the line.

Today is just another Friday in August. Drowsy and close. Office workers' minds are fixed on the weekend, clock-watching, waiting perhaps for a holiday if your finances have escaped the credit crunch and rising food and fuel prices. In the evening, trains will be littered with abandoned newspaper sports pages, all pretending interest in the football transfers.

For once it seems justified to repeat TS Eliot's famous lines: "This is the way the world ends/Not with a bang but a whimper."

But does it have to be this way? Must we curdle in our complacency and allow our cynicism about politicians to give them an easy ride as they fail to act in our, the national and the planet's best interest? There is now a different clock to watch than the one on the office wall. Contrary to being a counsel of despair, it tells us that everything we do from now matters. And, possibly more so than at any other time in recent history.

It tells us, for example, that only a government that was sleepwalking or in a chemically induced coma would countenance building a third runway at Heathrow, or a new generation of coal-fired power stations such as the proposed new plant at Kingsnorth in Kent. Infrastructure that is fossil-fuel-dependent locks in patterns of future greenhouse gas emissions, radically reducing our ability to make the short- to medium-term cuts that are necessary.

Deflecting blame and responsibility is a great skill of officialdom. The most common strategies used by government recently have been wringing their hands and blaming China's rising emissions, and telling individuals to, well, be a bit more careful. On the first get-out, it is delusory to think that countries such as China, India and Brazil will fundamentally change until wealthy countries such as Britain take a lead. And it is wildly unrealistic to think that individuals alone can effect a comprehensive re-engineering of the nation's fossil-fuel-dependent energy, food and transport systems. The government must lead.

In their inability to take action commensurate with the scale and timeframe of the climate problem, the government is mocked both by Britain's own history, and by countries much smaller, poorer and more economically isolated than we are.

The challenge is rapid transition of the economy in order to live within our environmental means, while preserving and enhancing our general wellbeing. In some important ways, we've been here before, and can learn lessons from history. Under different circumstances, Britain achieved astonishing things while preparing for, fighting and recovering from the second world war. In the six years between 1938 and 1944, the economy was re-engineered and there were dramatic cuts in resource use and household consumption. These coincided with rising life expectancy and falling infant mortality. We consumed less of almost everything, but ate more healthily and used our disposable income on what, today, we might call "low-carbon good times".

A National Savings Movement held marches, processions and displays in every city, town and village in the country. There were campaigns to Holiday at Home and endless festivities such as dances, concerts, boxing displays, swimming galas, and open-air theatre - all organised by local authorities with the express purpose of saving fuel by discouraging unnecessary travel. To lead by example, very public energy restrictions were introduced in government and local authority buildings, shops and railway stations. This was so successful that the results beat cuts previously planned in an over-complex rationing scheme. The public largely assented to measures to curb consumption because they understood that they were to ensure "the fairest possible distribution of the necessities and comforts of daily life".

Now, 2008, we face the fallout from the credit crisis, high oil and rising food prices, and the massive added challenge of having to avert climate change.

Does a war comparison sound dramatic? In April 2007, Margaret Beckett, then foreign secretary, gave a largely overlooked lecture called Climate Change: The Gathering Storm. "It was a time when Churchill, perceiving the dangers that lay ahead, struggled to mobilise the political will and industrial energy of the British Empire to meet those dangers. He did so often in the face of strong opposition," she said. "Climate change is the gathering storm of our generation. And the implications - should we fail to act - could be no less dire: and perhaps even more so."

In terms of what is possible in times of economic stress and isolation, Cuba provides an even more embarrassing example to show up our national tardiness. In a single year in 2006 Cuba rolled-out a nationwide scheme replacing inefficient incandescent lightbulbs with low-energy alternatives. Prior to that, at the end of the cold war, after losing access to cheap Soviet oil, it switched over to growing most of its food for domestic consumption on small scale, often urban plots, using mostly low-fossil-fuel organic techniques. Half the food consumed in the capital, Havana, was grown in the city's own gardens. Cuba echoed and surpassed what America achieved in its push for "Victory Gardening" during the second world war. Back then, led by Eleanor Roosevelt, between 30-40% of vegetables for domestic consumption were produced by the Victory Gardening movement.

So what can our own government do to turn things around today? Over the next 100 months, they could launch a Green New Deal, taking inspiration from President Roosevelt's famous 100-day programme implementing his New Deal in the face of the dust bowls and depression.

Last week, a group of finance, energy and environmental specialists produced just such a plan.

Addressed at the triple crunch of the credit crisis, high oil prices and global warming, the plan is to rein in reckless financial institutions and use a range of fiscal tools, new measures and reforms to the tax system, such as a windfall tax on oil companies. The resources raised can then be invested in a massive environmental transformation programme that could insulate the economy from recession, create countless new jobs and allow Britain to play its part in meeting the climate challenge.

Goodbye new airport runways, goodbye new coal-fired power stations. Next, as a precursor to enabling and building more sustainable systems for transport, energy, food and overhauling the nation's building stock, the government needs to brace itself to tackle the City. Currently, financial institutions are giving us the worst of all worlds. We have woken to find the foundations of our economy made up of unstable, exotic financial instruments. At the same time, and perversely, as awareness of climate change goes up, ever more money pours through the City into the oil companies. These companies list their fossil-fuel reserves as "proven" or "probable". A new category of "unburnable" should be introduced, to fundamentally change the balance of power in the City. Instead of using vast sums of public money to bail out banks because they are considered "too big to fail", they should be reduced in size until they are small enough to fail without hurting anyone. It is only a climate system capable of supporting human civilisation that is too big to fail.

Oil companies made profits when oil was $10 a barrel. With the price now wobbling around $130, there is a huge amount of unearned profit waiting for a windfall tax. Money raised - in this way and through other changes in taxation, new priorities for pension funds and innovatory types of bonds - would go towards a long-overdue massive decarbonisation of our energy system. Decentralisation, renewables, efficiency, conservation and demand management will all play a part.

Next comes a rolling programme to overhaul the nation's heat-leaking building stock. This will have the benefit of massively cutting emissions and at the same time tackling the sore of fuel poverty by creating better insulated and designed homes. A transition from "one person, one car" on the roads, to a variety of clean reliable forms of public transport should be visible by the middle of our 100 months. Similarly, weaning agriculture off fossil-fuel dependency will be a phased process.

The end result will be real international leadership, removing the excuses of other nations not to act. But it will also leave the people of Britain more secure in terms of the food and energy supplies, and with a more resilient economy capable of weathering whatever economic and environmental shocks the world has to throw at us. Each of these challenges will draw on things that we already know how to do, but have missed the political will for.

So, there, I have said "Fire", and pointed to the nearest emergency exit. Now it is time for the government to lead, and do its best to make sure that neither a bang, nor a whimper ends the show.

· Andrew Simms is policy director and head of the climate change programme at NEF (the new economics foundation). The material on climate models for this article was prepared by Dr Victoria Johnson, researcher at NEF on climate change. For regular suggestions for what individuals and groups can do to take action, and links to a wide range of organisations supporting the focus on the 100 months countdown, go to: onehundredmonths.org. The Green New Deal can be downloaded at neweconomics.org