Björn Lomborg has been a persistent global warming naysayer and his claims misrepresent my findings

-

- guardian.co.uk,

- Friday August 22 2008 18:00 BST

- Article history

The need for such a solution is supported by the best science available, including the report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), which was awarded the Nobel peace prize in 2007 and of which I was a member. The IPCC's message is clear: climate change is real, compelling and urgent - and we need a concerted, comprehensive and immediate effort to confront it.

But in the midst of this momentum and clarity, one voice has stood out as a persistent naysayer.

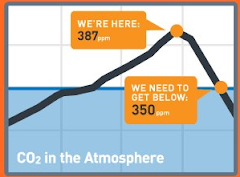

Bjorn Lomborg, author of The Sceptical Environmentalist, makes headlines around the world by arguing that capping carbon dioxide emissions is a waste of resources. He recently published a piece in the Guardian in which he dismissed efforts to craft a global carbon cap as "constant outbidding by frantic campaigners" to "get the public to accept their civilisation-changing proposals".

To support his argument, Lomborg often cites the Copenhagen Consensus project, a 2008 effort intended to inform climate negotiators. But there's just one problem: as one of the authors of the Copenhagen Consensus Project's principal climate paper, I can say with certainty that Lomborg is misrepresenting our findings thanks to a highly selective memory.

Lomborg claims that our "bottom line is that benefits from global warming right now outweigh the costs" and that "[g]lobal warming will continue to be a net benefit until about 2070." This is a deliberate distortion of our conclusions.

We did find that climate change will result in some benefits for developed countries, but only for modest climate change (up to global temperature increases of 2C - not the 4 degrees that Lomborg is discussing in his piece). But developed countries are relatively prepared to handle climate change's effects - they tend to be in colder areas, and they have the infrastructure to mitigate severe depletion of resources like fresh water and arable land.

That is precisely why our analysis concluded - and Lomborg ignores - that climate change will cause immediate losses for developing countries and the planet's most vulnerable, millions of whom are already facing challenges that climate change will exacerbate.

Downplaying the threat of climate change allows Lomborg to focus on his claim that

"unlike even moderate CO2 cuts, which cost more than they do good, we should focus on investing in finding cheaper low-carbon energy."He attributes this finding to our analysis as well, but again he overlooks a key element of our work.

Of course the world needs to make significant investments in cheaper, low-carbon energy. But making those investments without also implementing a constraint on emissions would fail to address the problem.

Our analysis assumed that over the next century, $800bn will be spent confronting climate change - $50bn spent on R&D in the next 5-10 years, and the remaining $750bn spent on adaptation and mitigation. This allocation of resources will reduce the cost of "clean" technology and increase the effectiveness of policies - like capping emissions - that are designed to reduce global CO2.

In short, we never advocated research into new technologies as a stand-alone way to fight climate change, nor did we accept Lomborg's dismissive attitude toward the threat climate change poses.

The negotiators in Copenhagen will need credible, accurately reported analyses upon which to base their discussions. This is not the time to deny the scope of the problem or belittle efforts to implement solutions. We need all options on the table. This was the message of the Copenhagen Consensus Challenge paper, and even a sceptical environmentalist should understand that.